Microwaves are good for reheating leftovers. They’re also good for blocking satellite signals and creating chaos in air traffic, transport, power supply and payment services. Andøya is where defence against such attacks can be trained for.

Three researchers sit inside a trailer on the edge of a cliff. The wind is tearing and pulling at the trailer. But they’re safe: The trailer is secured to the mountainside with two solid straps.

The Norwegian Sea stretches towards the horizon. Below them lies the settlement of Bleik.

They’ve set up a massive stand with eight antennae pointing ominously towards the cluster of houses below.

Down there, over 360 engineers from 120 technology companies and numerous public agencies are gathered.

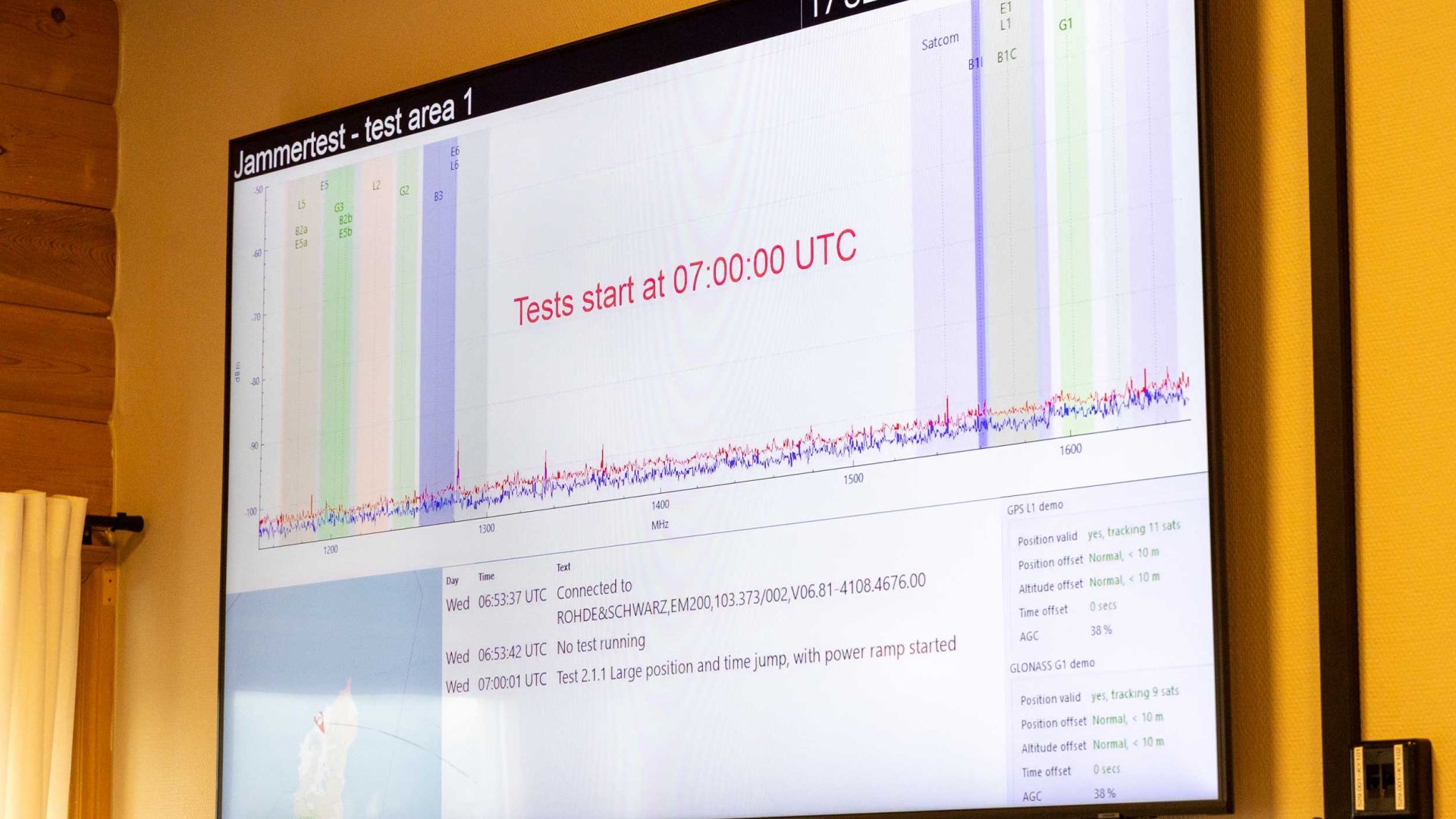

They’ve come to test how well their equipment functions when someone jams it – that is, when someone disrupts the satellite signals that provide accurate position and time to electronic equipment.

The researchers from FFI stand ready Their job is to be the villains. They’re going to jam and spoof. They’re going to create chaos.

In Ukraine, jamming (see the fact box below) and electromagnetic warfare (EW) are used to disable drones and enemy weapon systems.

But the technology we use every day is vulnerable to attack, as well. Smartphones, fitness watches, cars, aeroplanes, boats, payment solutions and power supplies all receive information about their own position and the correct time from satellites. When someone tampers with these signals, that could cause problems.

For the past four years, Norwegian authorities have organised ‘Jammertest’, a jamming test on Andøya in Nordland. Here, research, technology companies, and public agencies meet to find solutions that make the technology we depend on more secure.

Jamming is not something that occurs only in war and conflict. The Norwegian Communications Authority (NKOM) has long reported daily GPS disruptions caused by jamming in the airspace over eastern Finnmark. As recently as the week before this year’s test, a Widerøe flight en route to Vardø had to abort its landing due to Russian jamming.

In Bleik’s community hall, there’s bustling activity from early morning until late in the evening.

A 70-page transmission schedule indicates which positions and frequencies will be jammed when and where.

120 companies have sent their best engineers. Many return consecutive years to check whether their improvements work.

There are hugs all around when the researchers meet again at Andenes to set up their equipment for this year’s test.

In a grey car outside the community hall, three FFI researchers, each with their own laptop, monitor the situation. On the roof of the car, they’ve attached a series of different antennae and prototypes of protective equipment. The researchers are testing how the Armed Forces’ solutions for satellite communication holds up under jamming.

‘We rarely get a chance to test so intensively and thoroughly as here,’ says one of the researchers.

‘The only downside is the nice weather. You don’t get the proper Andøya feeling in sunshine and calm,’ he jokes.

The Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI) and the Finnish Defence Forces are also participating. Miikka Raninen from Finland is attending for the third time.

Finland is far ahead in electromagnetic warfare. They’ve brought along ‘Winnie the Spoof’, a car packed with transmitters and advanced equipment.

It’s part of a convoy with cars from car manufacturers and other firms leading and trailing Winnie while Winnie is attempting to disable the navigation systems of the surrounding vehicles.

‘It’s unique that academia, public authorities, industrial companies, and defence personnel from so many countries collaborate like this,’ says Raninen.

‘Although the threat is military, it affects the whole of society. We have a responsibility to contribute, describe the threat, and help the civilian side make the technology more resilient,’ he says.

‘It’s useful for us to be here. What we do is more sophisticated than just bringing Chinese and Russian jammers out here and simply switching them on. We send out test signals that are tailored to test the equipment that the participants have brought and tailored to different situations, such as approach flights. We ourselves learn a great deal during these tests.’

On Bleik’s sandy beach stands a helicopter from the Norwegian Air Ambulance Foundation. It’s dedicated to research and development.

In the back of the helicopter, there’s a suitcase that analyses what happens to the instruments when the helicopter experiences different types of jamming.

What they learn will be used to develop a predictive tool that warns pilots that they’re being jammed.

The data can also be entered into the HemsVX app so that other pilots will be aware of the danger.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration is one of eight public agencies collaborating on the jamming test. But why does the roads administration care about jamming?

‘We’re here to ensure that road traffic safety is heading in the right direction,’ says chief engineer Thomas Levin.

‘Modern cars are becoming increasingly high-tech. Development is moving towards self-driving vehicles. We’re not in a position where we can set our own requirements for the automotive industry or global standards. But we can ensure that stakeholders collaborate to develop more robust technology. Being involved in organising this test is a contribution to safer road traffic,’ says Levin.

Competition to be first and smartest

For FFI, the jamming test provides useful experience and a wealth of data to be used when researching electromagnetic warfare for the Armed Forces.

‘Jamming is a cat-and-mouse game, where new attack methods and new countermeasures and defence mechanisms constantly emerge,’ says FFI researcher Anders Rødningsby.

The jamming test clearly corroborates Rødningsby’s point. Different types of jamming can produce completely different results on different types of systems, watches, and phones from different manufacturers, depending on which protection mechanisms the systems have.

The video above shows four different GNSS receivers being spoofed. In other words, someone is tampering with the satellite signals that provide position and time. One receiver believes it’s heading straight out over the sea. Two others figure they’re on the mountain or in a marsh right by Bleik, respectively. A final one remains completely at rest.

The reason is that different GNSS receivers have different types of protection mechanisms, which in turn produce different results.

Running on water

There are several methods of protection. One is to use antennae or receivers that block or filter out jamming signals. Several antenna manufacturers were present at Bleik to test their products.

Another is to use what’s known as sensor fusion, which provides alternative solutions to fall back on when GNSS data can’t be trusted.

During the jamming test’s visitors’ day, the guests got to be spoofed. One of them started a Strava training session on their iPhone. The phone wasn’t fooled, though, and correctly stated that it was at rest outside the community hall at Bleik. The guest’s fitness watch, however, reported being out on a run, far out at sea, at a rather brisk pace. 2:30 per kilometre, to be precise.

‘This could be due to several reasons. One possibility is that the phone may use other GNSS signals than those actually being spoofed. In addition, the phone has motion sensors that should be able to tell that it’s not, in fact, moving, even though the GNSS receiver says it is,’ says Rødningsby.

If you want to learn more about jamming and how we can protect ourselves, you can watch the recording from the FFI breakfast seminar on how to protect society against jamming. Here, Nicolai Gerrard from NKOM and FFI’s Anders Rødningsby explain the technology in further detail.