Propaganda images reveal how terrorists think

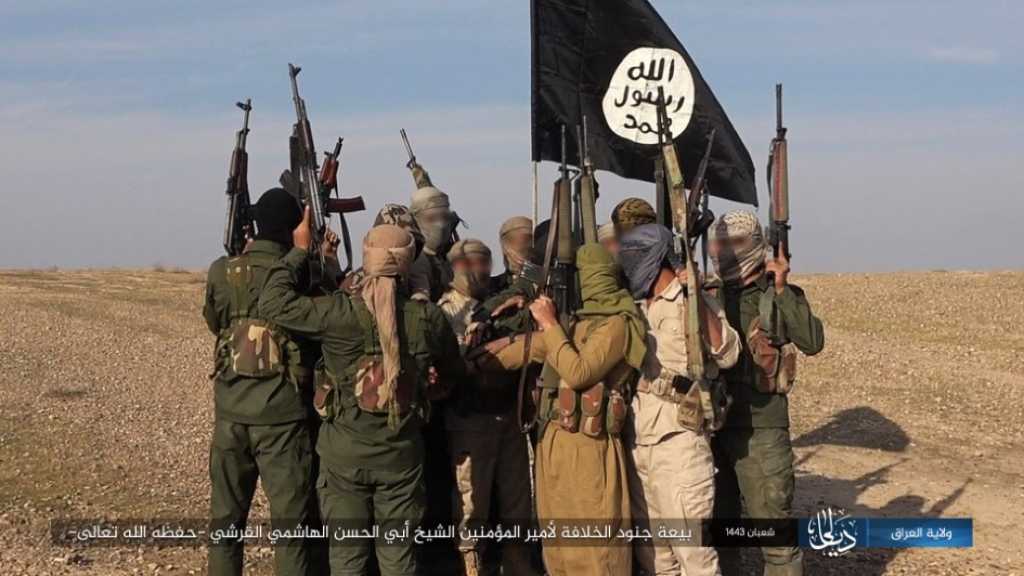

Researchers have used artificial intelligence to analyse over 30,000 propaganda images produced by the Islamic State (IS) between 2014 and 2022.

Propaganda is an important part of the operation of a terrorist organisation. They use text, video, audio, and images to not only spread fear, but also to recruit and build their image internationally. By using the internet and social media, even terrorist groups with limited resources can reach a global audience.

For researchers studying terrorist groups, propaganda material is an important source in understanding who the actors are, what they want, and how they operate. The challenge for researchers is the sheer amount of propaganda that is being produced, which makes it almost impossible to get an overview through manual means.

Because IS controlled a large area in Syria and Iraq for several years, they gained more resources and more members who could work as ‘journalists’ or content producers. Propaganda was clearly a prioritised area in the organisation, and the battles they were involved in provided them with plenty of raw material.

‘IS stood out because their propaganda was better than the content of earlier terrorist groups. They managed to create a “brand” and a linguistic and visual expression that appealed to the youth, combined with extremely brutal content where close-ups of killings were almost a given,’ explains Skretting.

Although the group is now marginalised in its original core areas in Syria and Iraq, its branches in other parts of the world have made significant progress – especially in Africa. IS still maintains a unified and substantial propaganda apparatus.

IS – a pioneer in terrorist propaganda

The researchers have based their work on the extensive image material published on IS’s official channels over the years. The dataset, consisting of 30,000 images, was fetched from an IS bot on Telegram.

‘IS has revolutionised how non-state actors and terrorist groups conduct propaganda. This is considered one of the keys to the group’s success,’ says researcher Vidar Skretting. He co-authored the report with colleagues and AI researchers Mathias Bynke and Bernt Ivar Nødland.

A dedicated IS social media

Initially, IS used established social media platforms like Twitter (X), Facebook, YouTube, and, later, the Telegram app to spread their content.

‘The spread of propaganda on social media is one of the reasons so many foreign fighters from around the world joined IS,’ says Skretting.

‘Today, it’s much more difficult for IS to reach out. Major social media platforms remove such content almost immediately after it’s posted. However, IS still manages to disseminate its content effectively through other channels, and it’s relatively easy for sympathisers to find them,’ Skretting adds.

IS spreads its propaganda through three main channels: ‘private’ social media platforms that they run on their own servers, bots on Telegram, and regular indexed websites.

‘The private social media platforms IS runs have been active for years. Telegram bots and the indexed websites are regularly taken down by administrators and authorities but are usually reopened by IS under different names shortly thereafter,’ says Skretting.

What have we learnt about IS from the images?

Once the images were sorted, the researchers wanted to answer the following question: How has IS’s image propaganda evolved from 2014 to 2022, and what does this development tell us about IS as a group?

‘The images IS publishes, the number of images published, and where they are published give us an indication of what IS is doing, how active they are, and in which areas they’re active,’ says Skretting.

He believes that insight into the development of terrorist organisations can be important in predicting their direction and strategies: By looking at the images from the African provinces where IS is on the rise, we might gain insight into where IS is heading in the future.

The analysis shows that in the early years (2014–2018), IS presented itself as both a military organisation and a civil state apparatus. This is linked to their attempt to build a ‘real’ Islamic state.

Since 2019, the focus has shifted. IS now presents itself almost exclusively as a military movement and insurgent group.

2015 was the year IS was most active in terms of propaganda. Nearly half of all the images in the dataset are from this year, which coincides with the time when IS was at the height of its power in Syria and Iraq. Thus, most of the images in the material are from Syria and Iraq.

‘The group has been defeated in their previous primary areas but is rebuilding in Africa. We also see this trend in the image material,’ says Skretting.

Activity was at a low point in 2020 but has since increased. The majority of images are now published in West and Central Africa. These differ from those produced in the Middle East in several ways.

‘There is much less focus on individual jihadists and martyrs. At the same time, the propaganda images are generally more brutal. They’re dominated by military content, reflecting the fact that they are most active as a military organisation,’ says Skretting.

Further development of the methods is needed

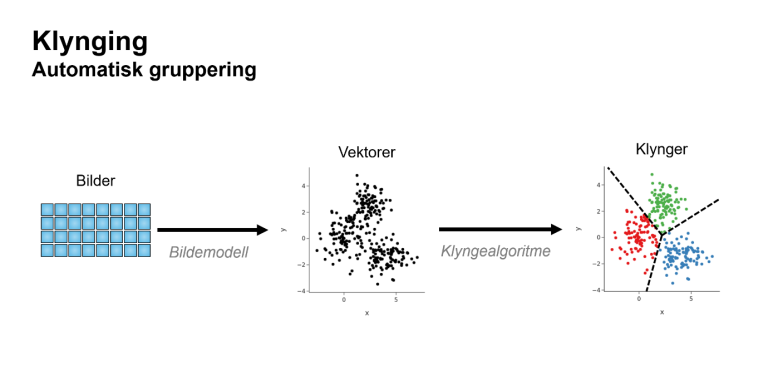

The researchers conclude that the combination of CLIP and clustering algorithms is an effective method for quickly analysing large amounts of propaganda images.

‘The division into clusters was not perfect. A certain proportion of the images appeared misclassified, and we had to implement mechanisms to filter these out. But the method helps to speed up the analysis,’ says Skretting.

He emphasises that the combination of CLIP and clustering algorithms can be used for more than analysing terrorist images.

‘The method is relatively simple and scalable. You can easily use it to sort image collections far larger than 30,000 images into thematic clusters. The method is particularly useful if you don’t know a lot about the content of the image material in advance.’

The researchers believe we should further develop machine learning methods to map propaganda from state and non-state actors.

‘This type of method is not only relevant for image analysis but also for getting an overview of large text, audio, and video materials,’ stresses Mathias Bynke.